Meritocracy, Educational Access and DIY U: Part One

I just returned from a swing around some more or less non-elite colleges in the Midwest where I faced a common objection to DIY U:

You talk about access. But the students being left out of the current system are the ones who need more one-on-one support, so how can online educational resources, even if they’re free, possibly help them?

To which my basic answer is: You got a better idea?

Either we use technology to bend the cost curve in higher education, or we resign ourselves to never having enough of it. For-profit colleges will continue, quite expensively, to take up the slack by targeting the students left out of the current system: working adults and the first in their families to go to college. I agree that it would be a good basic strategy to reallocate the $ saved through use of open educational resources toward one-on-one support and mentoring for the students who need it most.(I’m not sure I agree that these types of services could never be delivered digitally with economies of scale: For example at Miami Dade college where automated text messages follow up on students who miss class. But that’s another discussion).

Viewed this way, the creation of open educational resources from the Open Courseware Consortium to open-source LMS like Sakai, and even open study groups like OpenStudy could essentially be viewed as a necessary and productive resource transfer from rich schools to less well funded ones.

Gearing Up For Mozilla Drumbeat: How To Facilitate a P2PU Class

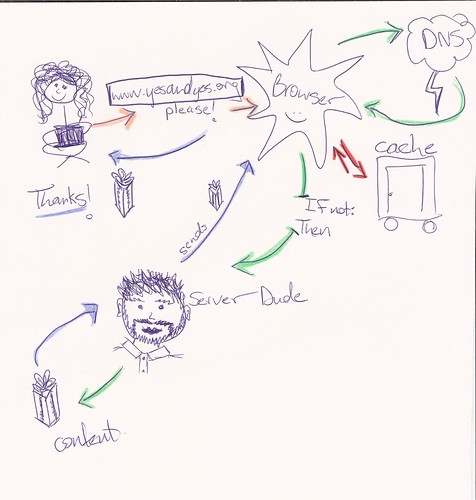

Image of P2PU class “Draw the Internet” assignment, via JohnDBritton on Flickr.

In preparation for the Mozilla Drumbeat Festival next month (coming up in just 13 days!! whoo hoo!!) i’ve been conducting preview interviews with participants. The best of these, as well as other Q&As, blog posts, Tweets, speeches, essays, and other contributions, will eventually go into the Festival Report, which I’ve been describing as a “quickbook.” It’s faster, looser, and more open than my normal writing methods–entirely fitting that all these experiments in open learning and teaching should be documented in a way that’s itself an experiment.

A couple of weeks I interviewed John D Britton, a programmer, champion couchsurfer and Bar Camp participant who got pulled into open ed more or less through this blog post.

I also dropped in on his P2PU/Mozilla School of Webcraft class, “Anatomy of A Web Request,” and talked over video chat to students from all over North and South America.

When I asked about his methods for teaching a P2PU class, Britton countered, “I tend not to use the term ‘teach’. I’m a facilitator. Part of the philosophy of P2PU is that everybody is equally responsible for their learning.” Still, he said, breaking out of that old paradigm–and figuring out what to keep from it– is an evolving process. His first P2PU course, “Mashing Up the Open Web,” he said, took far too much time. “I was online holding office hours every Sunday from 10 to noon. I was the single point of failure for the course–it was very top down, very traditional, and hard to keep up with.” In his current class, he’s giving the students more responsibility for discussing amongst themselves and critiquing each other, although as the facilitator he’s still responsible for giving out assignments and, importantly, imposing due dates. The due date, it turns out, is one aspect of the traditional education experience that’s still essential in the peer-to-peer learning world.

Britton, who dropped out of college himself and works for a company called Twilio, loves leading P2PU classes because, “Teaching something is the best way to learn.” For his next P2PU course he’s really putting that philosophy into practice. The topic is window farming, which he describes as “totally out of my knowledge domain… I want to learn how to do it, so I might as well document it and learn it with a bunch of other people.” Right on!

HELP Higher Education in Haiti

Crossposted from GOOD magazine.

“Almost no one is working on higher education overseas.” That’s what Conor Bohan, head of Haitian Education and Leadership Program, told me in his office last week. We met at the Clinton Global Initiative in September and bonded over this common interest.

Here’s the problem. The balance of power and wealth is shifting rapidly from industrial to postindustrial economies, and with it, the demand for a highly educated workforce. This is true around the world: a simple high school diploma is no more a guarantee of a living wage job in Haiti than it is in the US.

But most international education aid whether from governments, big foundations, or the World Bank, focuses, understandably, on the pressing need for basic literacy. What’s required is nothing less than a quantum leap for the higher education attainment rates in, say, sub-Saharan Africa (about 5 percent) approach those at the top of the heap (Canada and South Korea, above 50%).

Conor’s program, HELP, is trying to make a tiny difference in the poorest country in the Western hemisphere. He started it when he was working in Haiti as a schoolteacher and one of his star students asked him for $30 to enroll in secretarial school. After questioning her he learned that her real dream was to become a doctor–and today she is.

HELP accepts only students with straight A’s through high school. They received 350 qualifying applications for 30 slots last year. It costs a total of about $5500 a year to send a student to Haiti’s public university, or one of its Catholic or private institutions, and to provide them with funds for clothing, shelter, books, academic advising, and internships. HELP believes firmly in building up local capacity by sending students to college in-country, where the quality is said to be quite good–University of Miami president Donna Shalala has said,”The one institutional strength Haiti has had is its higher-education system.”

Graduates of HELP’s scholarship program increase their income from about $600 a year with just a high school diploma to about $14000 a year on average. That’s an incredible payoff, better than almost any social entrepreneurship program you could name. It seems like a good idea to me that they do it without creating debt for the students, unlike a microfinance student loan program called Vittana that has received a lot of attention. I’ve started talking to Conor about the possibility of connecting his students with academic advising, peer study groups, English classes, and mentorship opportunities over the Internet. If you have any ideas about this, get in touch. I also think sponsoring a HELP student would be an amazing fundraising project for a US college campus.

Live Streaming Event from Stanford U Today!

I’ll be streaming live from Stanford today at 3-4:30pm (6-7:30pm ET).

Here’s the UStream link.

Anya Kamenetz, author of

DIY U: Edupunks, Edupreneurs, and the Coming Transformation of Higher Education (Chelsea Green, 2010)

will be visiting the School of Education on

MONDAY 11 OCTOBER, 3 – 4.30 PM

CUBBERLEY HALL 115

She will receive critical commentary from sociologists

Michael Hout, UC Berkeley,

(an expert on inequality)

& Marc Ventresca, Oxford/Said Business School, (an expert on innovation and new markets).

E-Mentoring: Someone (Virtually) At Your Side

I’ve been thinking a lot about e-mentoring lately.

Probably the most common objection to the DIY U vision is the supposed lack of personal connection when people are learning online. This is an important concern. No matter where you are on your educational journey, having a mentor and advisor is key. And it’s exactly the students ill-served by the current educational system—because they are poor, they live in rural areas, are the first in their families to go to college, have learning disabilities or negative interactions with formal education—who are most in need of a stable person in their life who can provide encouragement, a sense of educational direction, or just a role model.

Yet it’s a mistake to assume this can’t be done online. Here’s a couple of examples that I’ve come across lately.

Last Wednesday I moderated a panel on “Democratizing Education: The Key to Global Economic Growth” at the Clinton Global Initiative. The star of the show was Vivian Onano, a sparkling young graduate of a Microsoft-sponsored computer lab program for girls in Kenya. They spend 9 months learning everything from Excel to business accounting and even a computer program that teaches them how to do AIDS education. At night the girls return to the lab and study. Vivian told me they hide under the desks when the lights are turned off so that they can stay in the lab until late at night, using the Internet for everything from research to Facebook! She went online to apply for colleges and was accepted on scholarship to Carthage College in Wisconsin, where she started this month in premed.

While on her first visit to New York City for CGI, Vivian wasn’t among strangers. She was staying with a woman in Rye, New York who had been her mentor for the past few years. Linda Lockhart of Global Give Back Circle, which runs the Microsoft-sponsored labs, says that each of her 270 girls is paired one on one with a mentor in the States. It’s a very serious relationship, at least a six year commitment from high school through post secondary school and getting launched, and yet they don’t normally meet face to face. The program was originally designed to work through letters, but when the girls get to the lab they are able to stay in much closer touch through email, Facebook, Skype chats and phone calls.

Later this weekend, I was talking about this idea with a friend of mine who is a PHD student at NYU. He said that since his undergraduate years at MIT he’s been involved with a program called Middle East Education Through Technology that teaches Israeli and Palestinian teens computer skills and has them work on projects together. While the students all work together with their American counselor/instructors during the summer sessions, the rest of the time they stay in touch via the Internet.

Finally, Seth Weinberger of Innovations for Learning, which I wrote about in Fast Company’s April issue, also runs a program that allows Chicago professionals to tutor public school kids over the Internet and phone. Kids as young as first grade talk to their tutors while the two of them read together or look at math problems on a shared desktop. Seth showed me a short video of the kids meeting their mentors for the first time at the end of the school year—hugs all around.

Why is this important? Having a mentor is part of an optimal educational experience, something that technology-assisted learners deserve to the extent possible. Also, the pool of potential mentors is larger if you make it something people can do over the Internet and phone—like the busy professionals in Chicago, who can help schoolkids from their desks instead of trekking back and forth to the schools in the middle of the afternoon. I’m thinking about signing up as a Global Give Back Circle mentor myself.

Join Me At The Mozilla Drumbeat Festival, November 3-5!

I’m excited to announce that i’m going to be participating in the first Mozilla Drumbeat Festival on the Future of Learning, Freedom and the Web, in Barcelona, Spain this November 3-5.

Mozilla is calling it a festival instead of a conference because they actually want to use it to build stuff, try stuff out, and get projects going. And there are some tremendously exciting projects already in the works. Peer2Peer University will be planning the next semester of their School of Webcraft, a free, open, online web development school that got going this fall;and a bunch of people will be working on a badge project to recognize informal learning; others will be building a global open courseware catalogue and discovery tool, others a mobile classroom in a van.

I’ve got a project too: A new book about the Future of Learning, Freedom and the Web. Mozilla is publishing it; it will be part document of the festival and part DIYU 2.0. I’ll be interviewing participants and collecting the best blogs, Tweets, wiki entries, and thoughts in all media on the state of learning, freedom and the web in 2010 and beyond.

If you’re interested in the conference or want to know more about the book, get in touch!

http://www.drumbeat.org/festival

Game Changers in Education

I am so excited about my panel tomorrow at the Clinton Global Initiative. You can watch the webcast live here and tweet your questions to #cgi10:

Also, you can vote for me as a Huffington Post Game Changer in Education

They wrote a lot of nice stuff about me.

but I recommend instead you vote for my CGI co-panelist Shai Reshef of University of the People. It’s an honor to be nominated alongside folks like him though!!!

Got Any Updates or Corrects for DIYU?

I’ve just returned from an amazing trip to South Dakota, and i got the great news in my inbox that DIYU may be coming up for reprint in a couple of months.

I’ve already been informed of two typos where I sadly messed up the names of Jeff Berger of KODA and Professor Gardner Campbell. Has anyone else out there spotted misspellings, typos, or facts that really need to be updated or corrected? I have until September 29 to fix them. You can leave them in the comments or email me at a kamenetz at fastcompany dot com.

This is for big boo-boos only–they want to keep the same page numbers if possible.

For those who are interested in a more complete large-scale update, watch this space–I may have some exciting news very soon.

What’s Up With Twentysomethings? In A Word, Economics

I can’t believe we’re going through this again.

I can’t believe we’re going through this again.

In January 2005, Time magazine featured on its cover a photo of a young man in a shirt and dress slacks sitting in a sandbox. The headline: “They Just Won’t Grow Up.” The article featured the research of one Jeffrey Jensen Arnett,PhD, a developmental psychologist who coined the term “emerging adulthood” to explain these puzzling, infantilized adults.

The cover story of the New York Times Magazine this weekend, already situated snugly at the top of the Most-Emailed List, is a near-exact repeat of this story from 5 years ago, this time asking “What is it About Twenty-Somethings?” Again Arnett is the resident featured expert. The Times’ only innovation, besides the slightly higher quality of the writing and the greater length, is tarting up the article with lots of sexy pictures of 20somethings (“I’m lying on my bed, all angsty! Look down my shirt!”) so readers can lust after them while simultaneously shaking their heads.

While they try on various social science hypotheses to explain this transition the overall tone of both articles is condescending, puzzled, frustrated, mocking. Both take the point of view of the print magazines’ aging readership: your mom, who wants you to get a job and an apartment and get married and give her grandchildren.

As I argued at great length in my book Generation Debt in 2006, and in dozens of articles for the Village Voice, Yahoo!, the New York Times, and the Washington Post dating back to 2004, the overwhelming reasons for this so-called “delayed transition” are economic. College costs 1000% more money than it did 30 years ago, yet it’s required for most living-wage jobs. Young people work longer hours while they’re in school, so it takes them longer to finish. Rent is higher too, and the youth unemployment rate is the highest for any age group. Young people have unprecedented amounts of student loan and credit card debt that persist into their 30s. Getting married, let alone starting a family, is difficult, even inadvisable, when you’re not financially stable.

Even when we as a nation try to remedy Generation Debt’s problems, we do so in a way that extends financial dependency. For example, the recent health care bill included a provision that young adults must be included on their parents’ health care policies until the age of 26. Why not mandate instead that the part-time service employers that overwhelmingly rely on young workers provide access to health care coverage?

There is no mysterious collective 20something malaise. The poor position of our nation’s future workforce is the outgrowth of decades of economic policy–the growth of consumer and national debt and the deterioration of the American job market, the protection of old-people programs like Social Security and Medicare and the faltering of opportunity-creating programs like education and health care for all. Maybe the Times should be talking to its own Paul Krugman, not a psychologist.

Or, if the Times editors wanted to emphasize the cultural and personal experience that emerges from this economic background, why not commission a young writer? Why is an article asking “What’s Up With Twentysomethings?” being written by a writer who is clearly at least in her 50s? I can think of half a dozen writers in their 20s who’d be great for the job. I’d have been happy to do it myself–I’ll be in my 20s for 3 more weeks.

Is TED the New Harvard? Reactions from Around the Web

(crossposted from FastCompany.com)

My story has occasioned a healthy amount of reaction around the web, including from TED and Chris Anderson himself.

First, the snark: Maura at The Awl (a commentary site run by ex-Gawkers) calls the story “breathless” and “smug”. Most of the commentators admit that they enjoy watching TED talks anyway. I batted back with some snark of my own but also tried to answer what i took as her serious point, which was that TED seems just as elitist as the old-line institutions it’s being compared with:

“I actually think we have similar concerns about elitism vs. openness.

My contention is that many of the cool things that TED does spread more widely than the cool things that Harvard does, because of its attitude toward openness and its use of social media.

Harvard has a crappy open courseware site–it’s very difficult to find and view many Harvard lectures online. MIT has the best open courseware site, but even the most-watched video lectures have been watched a few hundred K times, while the most watched TED talks have been viewed over 6 million times.

Lectures are admittedly a small percentage of the benefit offered by either TED or Harvard, but they’re not nothing. The spread of the TEDx platform with over 600 events worldwide offers a way for ever-more people to participate, often for free, in a much closer approximation to the TED experience. I would love to see Harvard & Yale try something like that.”

Open Culture , a cultural blog, took umbrage too: “Will watching 18 minute lectures – ones that barely scratch the surface of an expert’s knowledge – really teach you much? And when the 18 minutes are over, will the experts stick around and help you become a critical thinker, which is the main undertaking of the modern university after all?”

I responded: “I never claimed that watching TED talks=attending Harvard. If you read the article closely, I’m asking if *participating in* TED–and to a lesser but broader extent, TEDx–-confers a lot of the benefits of attending Harvard, albeit in abbreviated (and much cheaper) form. That means talking about the ideas with the presenters, including asking questions; forming relationships with fellow TEDsters; and having TED on your resume, which can open all kinds of doors.

In addition, I’m asking if there’s any way that Harvard and other universities can follow TED’s lead and open up to more people. When a single Harvard lecture has been viewed 5 million + times on YouTube, this goal will be closer to being reached.

TED videos have far more uptake than open courseware from MIT or anywhere else–over 300 million views–not only because the content is more entertaining but because they pay very close attention technically and production wise to what works well on the web.

And, with the TEDx program, TED has “released the platform” so that thousands of people, (over 600 events in the first year) , in countries around the world, are able to participate in something that’s often very very much like TED, and most of the time for free, or else for no more than $100. I would love to see Harvard, Yale, and MIT do that.”

Reihan Salam (who is a friend of mine) at the National Review and Matt Yglesias at the progressive blog Think Progress were less bothered by the piece’s tone per se, and more taken with what it might say about the role of the modern elite university in the 21st century.

“The success of TED doesn’t mean that traditional elite institutions don’t have a place. But it provides a very constructive kind of competition,” Salam wrote. “As TED’s “mindshare” expands, will will hopefully see more efforts like MIT’s OpenCourseWare, if only because elite schools don’t want to lose their relevance and their influence. Eventually, the mission of these schools, with their vast resources, will focus more on the wider public than on their own enrolled students, thus delivering more educational bang-for-the-buck. TED is, in a small but important way, teaching educators how to solve the problem of scalability.”

Not surprisingly, I think this is spot-on. I want to reemphasize what I think TED’s achieved with the TED talk. They’ve proved that there is a robust audience for semi-long form lectures on the web that pique people’s interest in topics like robotics, demography, physics and public health. But don’t ask me, ask the teachers of the Teaching With Ted wiki, an independent, self organized group of educators who use TED talks in their classrooms.

Yglesias argues that universities’ turn toward greater openness won’t happen automatically; we should direct philanthropy toward organizations that truly expand educational opportunity. I’m all for that.

Finally, TED’s Chris Anderson seems to be getting concerned that TED is being accused of overreaching. When the article came out, he Tweeted “Fast Company have just published

a truly amazing feature on #TED. Wow. http://bit.ly/aNOsQH.”

Today, he added, linking to Salam’s and Yglesias’s posts above, “For the record, we don’t for 1 min think “TED is

the new Harvard”! http://bit.ly/arU8Z1 Backlash! http://bit.ly/ciCJEV“

Duly noted. Those are Fast Company’s words, not TED’s. But I stand by the comparison, because I think it brings up interesting and provocative questions, and that’s what we’re here for.