Can the Ad Industry Save Education?

(crossposted from FastCompany.com).

This month we asked a bakers dozen of contributors for fresh ideas on how to reinvent education. Now a coalition of ad industry heavy hitters from Wieden + Kennedy to BBDO has come out with a major campaign to promote creativity in education.

To be clear, they’re not just looking to promote creative solutions to well-known problems like poor math scores and low and falling graduation rates. They’re looking for approaches to promote creativity itself–arguing, in a really gorgeous slide presentation, that creativity is the no. 1 competitive edge in the 21st century, and the prime element that’s missing from our standardized test- and state standards-ridden school system. A patron saint of the effort, and judge on the panel, is Sir Ken Robinson, whose TED talk to this point is one of the most watched ever.

“What drives us is the possibility of a platform

where the creative industries put their differences aside for one week

out of the year to collaborate on something that is larger than

ourselves and our business goals,” says Viktor Venson of multimedia and interactive agency Stopp, a driving force behind the campaign. ” If adopted, this would be an annual challenge asking the creative industries to respond to a burning issue or cause.”

As part of Social Media Week 2011, next week in New York City, No Right Brain Left Behind is challenging industry teams (advertising, interactive, marketing, design, what-have-you) to come up with products and approaches that work within or outside the existing school system. These will be piloted by the end of 2011.

I’m torn. I absolutely love the idea of moving our schools away from a relentless focus on tests of basic skills and toward approaches that emphasize play, risk-taking, collaboration, and the other skills that make work worth doing and life worth living. The very structure of this campaign, moving swiftly from design brief to execution, has the elegance of the American creative spirit at its best.

On the other hand, the interaction of the ad industry with schools has produced some not-so-pretty effects in the past (Channel One, anybody?) And lots of the problems in our public schools are problems of urban poverty and inequality that need to be solved with boring old tax policy, not jazzy new logos and apps.

I guess in the end I’ll go with optimism that No Right Brain Left Behind produces some interesting new opportunities and turns on some new creative minds to the problems in our education system. The more eyeballs on this issue, the better.

How To Have A Drumbeat Festival

(One of the features in the Drumbeat book will be a series of how-tos. One of the biggest “how-tos” in the book will be

how-to: Create a Drumbeat Festival. Here’s my first draft, for your feedback, especially if you were at the fest: )

how-to: Create a Drumbeat Festival.

purpose: start solving problems together and build a broader movement for change.

difficulty: Difficult, but fun.

who: 40 to 1000 people with different skills and interests including group facilitators. A mix of idea people and hands-on people, seasoned leaders and eager beginners. Drumbeat Festival 2010 featured 430 participants, including 40 volunteers, from 40 countries and 30+ participating organizations.

Time: 9 months to plan; 2 - 4 days to pull off.

materials: Space (for example the MACBA, FAD, courtyard and surrounding cafes, restaurants and tapas bars of Barcelona’s Raval district). Whiteboards. Laptops. Markers. Post-it notes. Wifi. Coffee. Pastries. Wine.

Step 1: Identify broad themes of shared, vital concern for all participants, ie Learning, Freedom, and the Web.

Step 2: Invite “space wranglers” to host spaces or “tents” relating to 1, 2, or all 3 of the main themes. Each should be dedicated to prototyping, designing, and creating solutions.

Step 3: Adopt Allen Gunn (“Gunner’s”) model for group faciliation, informed by the civil-disobedience training of the Ruckus Society and other left-wing organizing and consensus-based models.

-

Step 3a: “A bunch of people sitting and listening to one person talk is one step below a crime against humanity.” Minimize plenary sessions to “take the head off the event.”

-

Step 3b: “focus on respect” for all participants, volunteers, organizers. “If you are the most knowledgeable your job is to do the most listening.”

-

Step 3c: “focus on jargon” to make the dialogue as accessible as possible. Attempt to make translation available.

-

Step 3d: “Love-bomb” participants whenever appropriate with clapping and cheering. Conversely, make one person a designated “lightning rod” for complaints so negative energy is channeled constructively.

Step 4: For scheduling, draw on free-form “bar camps” and “unconferences” popular in the web community. Include open sessions with agendas defined by participants. Make the schedule an updatable-in-real-time wiki and/or eraseable whiteboard.

Step 5: Give each space a deadline to present results to the group at the end of the festival. Support those who want to join a team or continue working on a project, and publicize their efforts.

Step 6: Celebrate and document!

Tips and tricks: ??? How will you know when you've succeeded:???

How to Write a How-To

As mentioned before, a major component of the Drumbeat Learning, Freedom, and the Web book will be how-tos that people can use in their own learning situations (classrooms, workshops, online book clubs, whatever).

For example: How to adopt an open textbook; how to play with Arduino; how to create and award a badge; and even how to start a Drumbeat festival.

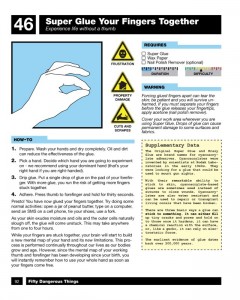

What are the basic components of a how-to? After looking at Instructables, Make magazine, Howcast videos, and other sources online, here’s what I”ve come up with:

1) Some indicators of the degree of difficulty, potential hazards, category of the how-to, and the time it takes. Symbols are helpful

2) Materials/tools needed.

3) Step by step instructions.

Anything I’m leaving out?

Update: Roger Schonfeld asked me to clarify: “We are a bit confusing – ITHAKA is the larger not-for-profit organization, of which Ithaka S+R, our strategic consulting and research service, is but one of several services.”

On Friday, with fresh snow on the ground, I trekked uptown to the Mellon Foundation for my first ever telepresence presentation. It felt very strange to be presenting my slides to an almost-empty room–the oddity of the technology meant that I had to look at a big image of myself, not of the audience, which was located in I think 5 or 6 different states.But it worked fairly well all things considered.

Anyway, the Q&A was much more interesting, I thought. Bryan Alexander gave a recap of the whole afternoon here.

Roger Schonfeld, of Ithaka, which is similarly dedicated to “ help[ing] the academic community use digital technologies to preserve the scholarly record and to advance research and teaching in sustainable ways” , saw on Twitter that I was at Mellon and invited me to walk across the courtyard and say hi–this is on 62nd street in Manhattan. So we chatted a bit about Taylor Walsh’s new book, Unlocking the Gates, from Princeton University Press, which I gather Ithaka supported her to write. It’s a great detailed look at the spread of open courseware programs from the institutions’ point of view. I plan to look back at the book in more detail soon.

“Ithaka S+R focuses on the transformation of scholarship and teaching in an

online environment, with the goal of identifying the critical issues facing our

community and acting as a catalyst for change.

We pursue projects in programmatic areas that are critical to academic work:

Sustainability of Digital Resources, The Role of the Library, Practices & Attitudes

of Faculty Members and Students, Teaching & Learning with Technology, and

Scholarly Publishing.”

Learning, Freedom and the Web Book Sprint–You Can Help!

So I flew up to snowy Toronto to spend all day yesterday at Mozilla’s offices in a design sprint for our Learning, Freedom and the Web book. I’d never been part of a “design sprint” before so I didn’t really know what to expect, but luckily our awesome designer Chris Appleton took charge and it turned out to be really fun and productive to boot! Basically we spent the entire day going over each page of the manuscript from a conceptual to a nuts and bolts level–identifying key concepts, looking at the Flickr pool for ideas, and sacrificing many Post-it notes in the process. Here’s some of our take-homes:

- Learning, Freedom, and the Web is about verbs, not nouns; solutions, not problems.

- We think there’s a huge silent (or not-so-silent) majority of educators out there who see the need for these kinds of changes in the world of education. We’d love for this book to be a rallying cry–a “hallway-waver” in Mark Surman’s words, something that people hold up to say “This is what I have been talking about!”

- With that in mind, a major recurring feature of each chapter is going to be how-tos. We won’t just explain the Badge Lab; we’ll give a few steps to show you how to get students to award badges in your classroom. Some DIY inspiration: Make Magazine, Instructables, Epicurious, and Fifty Dangerous Things You Should Let Your Children Do.

There’s also going to be a meta-how-to element where we explain how to put a Drumbeat-style festival together.

What do you think about the How-To idea? What needs to be included to make this actually useful?

I want to thank everyone from the community who’s provided feedback so far, and to let you know that there are two upcoming opportunities to get involved.

- We’ll be having community design/edit sprint phone calls on Thurs Feb. 3 and Thurs Feb. 24 at 7 pm ET. We’ll be going over specific chapters in each call, TBA. If your project or group is represented, we’d especially like to get your feedback/buy-in and we’ll be reaching out to you. Ben Moskowitz is in the process of putting the manuscript up on a public Etherpad, so anyone can check it out at any time.

- Right now: Nominate images for inclusion in the book! Go to this Etherpad and add links from Flickr or blogs to images you like, or email me with files.

Podcast interview on DIY U

http://www.blubrry.com/beyond50/916474/episode-275-diyu-do-it-yourself-university/

Revised: Intro to Drumbeat Book

Happy Holidays!

New revised version, love to get your take, and thanks again for everyone’s fabulous comments so far. They have been extremely helpful.

Barcelona, Fall 2010:

Learning and the Web. Two powerful forces of change converge in a public square. Their dimensions are unpredictable, and many of the outcomes of their convergence will be unintended, but this experiment is not entirely uncontrolled. Like Doc and Marty McFly in Back to the Future, the team has calculated the likely conditions, wired in all the right connections. When lightning strikes, we’ll be ready.

Learning: The natural process of acquiring knowledge and mastery.

Change rumbles like a seismic wave from the basements of the ivory tower, and the schoolhouse down your block. The demand for access to both existing and new models of learning is rising as uncontrollably as the average temperature throughout the globe. The traditional educational ecosystem is edging toward collapse. Fifty million university students in 2000 will grow to 250 million by 2025. The graph of educational costs is a hockey stick–headed straight up. Four hundred million children around the world have no access to school at all. No country in the world has a plan to fix this.

Meanwhile, informal learning–the kind we do all day every day, as long as our eyes are open and we’re not in school–is going through a Cambrian explosion in hackerspaces, libraries, museums, basements and garages all over the world. “How to” is one of the top searches on Google. YouTube hosts millions of videos that can teach you to deliver a baby or solve a Rubik’s cube. An entire generation of Web geeks is functioning more or less self-taught, because traditional curricula can’t keep up with the skills they need.

Which brings us to the second vector, arcing overhead–an invisible mesh of electrical signals that connect the people in this square to each other and to the world. Otherwise known as the web.

The Web: a system of languages, standards, and practices held in common that allow people to invent, access, connect, and bend things in the digital world.

Since its birth 25 years ago in a nuclear research lab in Switzerland, the web has grown beyond the grasp of the most hyperbolic metaphor and the expectations of the most rabid futurist (not that they don’t try). It’s more than fulfilled the promise that Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Caillou wrote in introducing their creation: “The World-Wide Web was developed to be a pool of human knowledge, and human culture, which would allow collaborators in remote sites to share their ideas and all aspects of a common project.” Today, 240 million unique sites are accessed by 1.75 billion people around the world; 35 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube, the most popular video site, every minute. The creation of wealth, beauty and human connection is ongoing on an unprecedented scale.

As more and more of us live, work, create, socialize, shop, bank, and, yes, learn online, the web gets stronger. Today the architects of the web are increasingly drawing the parameters of private and public life, and often for corporate profit rather than public benefit. The very principle that makes the web so vast and so powerful–the open structure, held in common, that allows anyone to access and contribute–is under threat as never before. The response is to assert our freedom.

Freedom: the intellectual, creative, political, or economic ability to access, create and remix knowledge–basic to learning, and the basis of the web.

Beyond the realm of hackers, programmers and developers, who are the natural allies of this kind of freedom? Who else believes in openness, innovation, sharing, remixing, participation by all? Who can be convinced to fight for it?

There are many possible answers to that question: journalists, artists, filmmakers, political activists. But the decision to start the Drumbeat by rallying the avant-garde of teachers and learners was by no means arbitrary. There is alchemy in the meanings and meetings of Learning, Freedom, and the Web.

LearningXFreedom: Education is civilization. Human culture can neither perpetuate or evolve without it. “Learning” is education plus freedom. It challenges authority by putting the learner first. Result: accelerated evolution.

FreedomXWeb: The Web requires freedom: transparent, remixable, innovative, accountable, public domain. View Source means you can see how it’s made and get your hands dirty fixing it.

WebXLearning: Their fundamental shared missions: To connect people across time, place, all barriers; to make available all human knowledge.

LearningXFreedomXWeb Learning gets more agile, more active, more participatory, more like the web. The web discovers its public mission and its place in human history. Everyone gets to invent their own end to the story.

Beautiful future(s), but a lot of hard work. Which is fortunate, because working and creating together is, generally speaking, the best way to form relationships, to build communities, and even to learn.

So here’s the complete Drumbeat formula for catching lightning: throw together educators and techies, both committed to innovation in the public interest; guzzle coffee, snarf tapas, chat and make friends; but also actually make stuff using open-source technology. The design brief is to develop new tools and practices that can supplement, optimize, and/or replace the traditional trappings of the education system, from diplomas and textbooks to lectures and lesson plans–the better to serve learners’ needs for learning, socialization, and accreditation in open-source fashion. And amidst the code sprints, why not write a wish list too: What tools remain to be developed to allow learners of all ages to form the questions that are most salient to them, find the answers they need, build skills, and present themselves for a community’s stamp of approval? What allies and teams need to be formed to make these things happen?

And thus, if successful, the agenda of two days becomes the manifest of a much greater voyage: A call for all those who care to spread Webcraft literacy, to learn by making stuff together, to keep the Web free by making it ourselves, to shape society through more democratic design, to pull learning out of the 15th or 19th century and into the 21st, to find strength in diversity, and to think critically about–and tell joyful stories about–all this doing and building and learning and making and sharing, the better to get more people involved.

So lightning struck the clock tower, two worldviews faced each other in a public square, and Drumbeat was born.

Or in the opening-night words of Mark Surman, director of Mozilla Foundation and Drumbeat’s visionary, as he shouted over the crowd, cheeks shining with sweat, in the high, echoey atrium of Barcelona’s Museum of Contemporary Art, “The future of the web and future of learning are intertwining. People here are creating that future.”

Twitter for Books!

That’s what Enric Senabre Hidalgo is calling PliegOS.

“a simple sheet of paper that once folded turns into a microbook (a real pocket-size one, indeed). It only needs a printer, a little do-it-yourself and an average 10 minutes for reading it.”

(Pliego is Spanish for octavo, one of the earliest types of books, printed and folded but not bound. They were popular at the time of Shakespeare.)

(Pliego is Spanish for octavo, one of the earliest types of books, printed and folded but not bound. They were popular at the time of Shakespeare.)

Hidalgo created a Pliego from Ismael Peña-López‘s Drumbeat festival blog series, which are here, or better yet you can print them out and make your own Pliego here. They are excellent.

HowTo pliego from pliegos on Vimeo.

Why Pliegos? Why printing at all? It’s for saving something worthwhile enough to read later, or to physically give someone else. You know, like a book. But smaller, for our impatient tl;dr age.

“Pliegos can be collected like stamps or stickers, but once read we strongly emphasize to leave them in the public space. Like an anonymous gift for a stranger reader. Specially if they contain text extracted form the Internet: turning this way the digital into physical, like a paper bridge between both worlds.”

Presenting: 1st Draft of Intro To Learning, Freedom and the Web!

Update: I’ve revised in response to comments below through 12/17. Thanks, everyone!!

I am liveblogging the manuscript process of writing Learning Freedom and the Web: The Book. Previous posts here and here. Your comments and editing suggestions are welcome, nay, encouraged, nay, begged for. You can also find a directly editable version of this text at this Etherpad.

Barcelona, Fall 2010:

Two powerful vectors of change converge in a public square. Although the forces are unpredictable, and many of the outcomes of their convergence will be unintended, this experiment is not entirely uncontrolled. Like Doc and Marty McFly in Hill Valley, the team has calculated the likely conditions, wired in all the right connections. When lightning strikes, we’ll be ready.

The first vector rumbles like a seismic wave from the basements of the ivory tower and the schoolhouse down your block. The demand for access to both existing and new and better models of learning is rising as uncontrollably as the average temperature throughout the globe. The traditional educational ecosystem is edging toward collapse. Fifty million university students in 2000 will grow to 250 million by 2025, and the graph of educational costs is a hockey stick–headed straight up. Four hundred million children around the world have no access to school at all. No country in the world has a plan to fix this.

Meanwhile, informal learning–the kind we do all day every day, as long as our eyes are open and we’re not in school–is going through an unprecedented Cambrian explosion. “How to” is one of the top searches on Google. YouTube hosts millions of videos that can teach you to deliver a baby or solve a Rubik’s cube. An entire generation of Web geeks is functioning more or less self-taught, because traditional curricula can’t keep up with the skills they need.

Informal learning really glows with possibility when it meets hardcore learning materials.

For the past ten years, the Open Educational Resources (OER) movement has released thousands of entire courses from pre-K to PhD–lectures, exams, serious games, and everything in between–that can be freely shared under licenses like Creative Commons. Free textbooks are a potent gateway drug: OER already has support from tens of foundations, hundreds of schools and dozens of governments. Obama’s Department of Education has thrown its weight behind the cause of open licensing all educational content created with government funds.

Now, innovators are found thick on the ground both within and outside the academy. Open learning and open courseware couldn’t exist without the network of passionate, committed educators employed in traditional institutions, like Davidson and Wiley, for two.

Yet even as the ground shifts under its feet, formal education as a whole has its head stuck in the sand. There’s a little debate going: Do today’s prevailing schooling models owe more to the monks of the 1400s or the bureaucrats of the industrial revolution?

The problem is ancient, says David Wiley, professor at Brigham Young University and one of the godfathers of open educational content. “About 500 years ago the primary mode of teaching in the university was to come in with blank sheets of paper and listen to the professor recite from a manuscript so you could make your own copy of the book,” he told the crowd on Drumbeat Festival’s opening night. “There was an opportunity 500 years ago with the invention of the press to radically change education. But that didn’t happen. The lecture is still the primary model. Now we have the birth of the Internet. If we only get these opportunities twice a millennium we should try to use them.”

Cathy Davidson of Duke University, nominated to the National Council on the Humanities, and a proponent of storming the academy from within, focused on a different moment of stuckness in her electric Drumbeat keynote. “Virtually every feature of traditional formal education was created between 1850 and 1919 to support the Industrial Age. The whole basis of assessment is the standard deviation, the invention of Francis Galton! A eugenicist who believed the English poor should be sterilized! We’re stuck with Henry Ford’s assembly line from kindergarten through grad school! But our world has changed! With the Internet we don’t need the same kind of hierarchical structures.”

The diagnosis is different, but the prescription is the same. Both Davidson’s and Wiley’s accounts point to the second vector.

Arcing over the hilltops: It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a lizard! It’s the ongoing creation of the open web!

Learning, Freedom and the Web is the theme of the first Mozilla Drumbeat Festival. Mozilla Drumbeat is “a series of practical projects and local events that gather smart, creative people around big ideas, solving problems and building the open web.”

Mozilla is a giant nonprofit open source software project. Together, thousands of people, employees but mostly volunteers, create Firefox, the number two web browser by market share, used by 400 million people worldwide. This is open source–a new way under the sun of organizing creative work with broad participation, all enabled by transparency. And in its maturity, a movement has grown out of this work, a worldwide alliance of people dedicated to keeping a part of the web transparent, held in common, and freely remixable by individuals. Oh yeah—and awesome.

Mitchell Baker, Mozilla’s founder and chief lizard wrangler, never takes a stage without thanking the volunteers that make it all possible. As she explained onstage in Barcelona, “Mozilla is about trying to build a part of the web that allows individuals to move from consumption to creation. We’re nonprofit not because it’s easy but because it represents what we’re trying to do. The Internet is so important that we believe that part of it should be a public asset.”

Their successes led Mozillians to ask, what else can openness do?And the battles they were constantly engaged in to protect the cause of Internet openness led them to ask: Beyond the realm of hackers, programmers and developers, who are our natural allies? Who else believes in openness, innovation, sharing, democracy, participation by all? Who can be convinced to fight for it?

There are many possible answers to that question: journalists, artists, filmmakers, political activists. But the decision to start the Drumbeat by rallying the avant-garde of teachers and learners was by no means arbitrary. The two groups have two important shared values and two shared tasks before them. You could call them the Four Freedoms.

- Freedom of Speech: The Internet transforms how we connect and share information; these are the defining tasks of education.

- Freedom of the Commons: Both the open web and education must balance their public mission with market forces.

- Freedom to Build: The architects of the Web are increasingly designing the parameters of private and public life. A key hacker value is that the Web is something WE Build. But for that openness to be meaningful, more people need the skills to participate. That’s where education comes in.

- Freedom to Transform: Formal education just happens to be the defining institution of any given civilization. It’s the machine that preps children to enter all the other institutions: the marketplace as workers and consumers, the government as citizens, or if they come in below grade, the welfare systems, the courts, and the jails – check out here for further information. So, if you really believe in the promise of the open Internet—that this is the birth of a new kind of institution, a really new way of organizing human endeavor–then an education revolution is not only essential, it’s all but inevitable.

Inevitable, but that doesn’t mean it won’t be a lot of hard work. Which is fortunate, because working and creating together is, generally speaking, the best way to form relationships, to build communities, and even to learn.

So here’s the complete Drumbeat formula for catching lightning: throw together educators and techies, both committed to innovation in the public interest; guzzle coffee, snarf tapas, chat and make friends; but also actually make stuff using open-source technology. The design brief is to develop new tools and practices that can supplement, optimize, and/or replace the traditional trappings of the education system, from diplomas and textbooks to lectures and lesson plans–the better to serve learners’ needs for learning, socialization, and accreditation in open-source fashion. And amidst the code sprints, why not write a wish list too: What tools remain to be developed to allow learners of all ages to form the questions that are most salient to them, find the answers they need, build skills, and present themselves for a community’s stamp of approval? What allies and teams need to be formed to make these things happen?

And thus, if successful, the agenda of two days becomes the manifest of a much greater voyage: A call for all those who care to spread Webcraft literacy, to learn by making stuff together, to keep the Web free by making it ourselves, to shape society through more democratic design, to pull learning out of the 15th or 19th century and into the 21st, to find strength in diversity, and to think critically about–and tell joyful stories about–all this doing and building and learning and making and sharing, the better to get more people to notice and get involved.

So lightning struck the clock tower, two worldviews faced each other in a public square, and Drumbeat was born.

Or in the opening-night words of Mark Surman, director of Mozilla Foundation and Drumbeat’s visionary, as he shouted over the crowd, cheeks shining with sweat, in the high, echoey atrium of Barcelona’s Museum of Contemporary Art, “The future of the web and future of learning are intertwining. People here are creating that future.”

Where My Forward-Looking Intellectuals At?

(UK Tuition Riots via andymoss461 on flickr)

My sister (whose blog is pretty awesome) shared this on Google Reader:

Walter Russell Mead in The National Interest (h/t: Boston Review):

[T]he biggest roadblock today is that so many of America’s best-educated, best-placed people are too invested in old social models and old visions of history to do their real job and help society transition to the next level. Instead of opportunities they see threats; instead of hope they see danger; instead of the possibility of progress they see the unraveling of everything beautiful and true.

Too many of the very people who should be leading the country into a process of renewal that would allow us to harness the full power of the technological revolution and make the average person incomparably better off and more in control of his or her own destiny than ever before are devoting their considerable talent and energy to fighting the future.

I’m overgeneralizing wildly, of course, but there seem to be three big reasons why so many intellectuals today are so backward looking and reactionary.

First, there’s ideology. Since the late nineteenth century most intellectuals have identified progress with the advance of the bureaucratic, redistributionist and administrative state. The government, guided by credentialed intellectuals with scientific training and values, would lead society through the economic and political perils of the day. An ever more powerful state would play an ever larger role in achieving ever greater degrees of affluence and stability for the population at large, redistributing wealth to provide basic sustenance and justice to the poor. The social mission of intellectuals was to build political support for the development of the new order, to provide enlightened guidance based on rational and scientific thought to policymakers, to administer the state through a merit based civil service, and to train new generations of managers and administrators. The modern corporation was supposed to evolve in a similar way, with business becoming more stable, more predictable and more bureaucratic.

Most American intellectuals today are still shaped by this worldview and genuinely cannot imagine an alternative vision of progress. It is extremely difficult for such people to understand the economic forces that are making this model unsustainable and to see why so many Americans are in rebellion against this kind of state and society – but if our society is going to develop we have to move beyond the ideas and the institutions of twentieth century progressivism.

I profoundly disagree. It’s true that there are a lot of smart people who are overinvested in the past. There’s also a fascinating class of new intellectuals who are completely dedicated to the future–multicultural, open, transparent, data-driven, economically balanced and just, innovative & multidisciplinary, sustainable, networked. It’s just that they’re often not credentialled in the old-school way, or if they are, they’ve repudiated that type of thinking (which is how they got to be such interesting thinkers), so maybe they’re not visible to this guy’s outdated definitions of “intellectual” or “best-educated.”

The blind spot in his argument is that the now woefully outdated program of the “advance of the bureaucratic, redistributionist and administrative state” begins with universities. “Credentialed experts” come from credentialed universities. Universities are the ur-”institution of twentieth century progressivism.”

It doesn’t mean I want to bomb the welfare state, destroy the institutions of 2oth c progressivism before anything stable has arisen to take their place. People suffer when you do that and they get pretty upset too (see the tuition riots in the UK).

It’s just that if we can agree that this is a tired way of thinking we should be able to agree that we need new kinds of tools, practices, resources and conversations to support new kinds of thinking. I avoid saying “new institutions” because I think what arises to replace the current institutions, like the university, may be unrecognizable as such.